The word écorché embodies a paradox between sound and meaning. Though musical to the ears, it is a term that cuts through the outer layers of appearance to examine the mysteries within. The French term écorché refers to the appearance that the body has been skinned to reveal its complex muscles and bone structure [1]. This centuries-old study remains a common practice for visual artists seeking to better understand the body and produce more realistic depictions in their work.

When and where did écorché begin?

Image 1. Example of illustration for TCM. Source.

Écorché is said to date back to ancient Greece [2], but this discipline also has origins in China [3]. During the Han Dynasty, an emperor called for the extensive dissection of a human body to document organ and blood vessel functions. The information captured in this study informed long-standing Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practices such as acupuncture.

In 1231, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II ordered mandatory human dissections to take place at least once every five years and required all medical students to attend [4]. This activity fueled the subsequent artistic engagement with human anatomy that flourished during the Renaissance in the 15th and 16th centuries.

With the rebirth of classicism came a quest for mathematical and anatomical perfection in all art forms. Artists became fascinated with movement and gestures, seeking to create the most realistic and sculptural depictions of the human body. During this period, the practice of studying cadavers as part of artistic instruction was popularized in Western culture and adopted by many successful artists.

The écorché works created throughout the Renaissance became extremely influential in the advancement of science, medicine, and art. They were also helpful resources for medical students faced with cadaver shortages.

Early écorché artists

Image 2. Closeup of Mosè di Michelangelo. Source.

Italian Renaissance Architect Leon Battista Alberti believed that painters should begin all nude studies with what lies beneath the skin. Michelangelo Buonarroti’s cadaver studies and écorchés informed his famously lifelike drawings, paintings, and sculptures. When sculpting his statue of Moses for the Tomb of Pope Julius II, Michelangelo included a subtle gesture to showcase his advanced understanding of the human body – a raised pinky [5]. This movement causes a specific muscle group in the forearm to visibly flex, a detail featured in Moses’ meticulously sculpted arm as it rests on a tablet bearing the Ten Commandments.

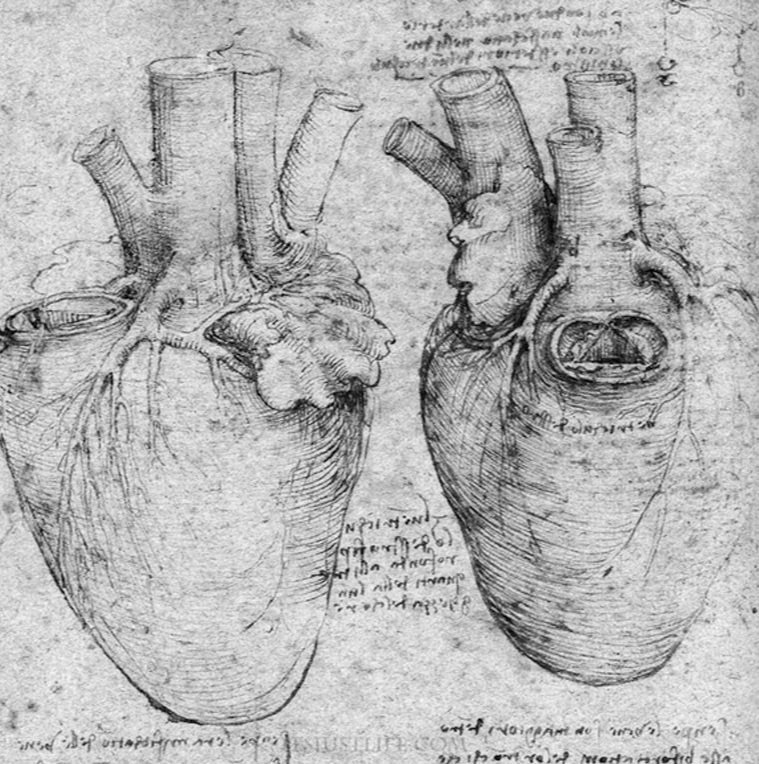

Image 3. Drawing and annotations of the human heart by Leonardo. Source.

Leonardo Da Vinci created some of the most well-known and highly regarded écorchés in history. Similar to Michelangelo, Da Vinci’s mastery of the human form is attributed to his hands-on experience with cadaver dissection. Da Vinci’s drawings were often accompanied by comprehensive notes on his observations and discoveries. He is credited with illustrating and documenting the coronary sinuses roughly 200 years prior to their official identification by anatomist Antonio Maria Valsalva [6]. The artist’s écorché works are published in textbooks and other medical resources that are still used today.

How were early écorché works received?

Image 4. Illustration from De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem. Source.

In 1543, anatomist Andreas Vesalius printed De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (“The Seven Books on the Structure of the Human Body”), a groundbreaking resource that publicized his findings from dissections alongside écorchés illustrating the inner workings of the human body [7]. His contributions to science and medicine secured him a position as the household physician to Holy Roman emperor Charles V [8].

However, this type of research was not always widely accepted or revered. For hundreds of years, human dissection was prohibited by the church due to the belief that the body and soul were one [9]. Cadavers were also hard to come by once anatomical studies rose in popularity and researchers resorted to unethical practices. Michelangelo creatively worked out a unique arrangement with the convent of Santa Maria del Santo Spirito that allowed him to study their corpses after sculpting their Basilica’s crucifix.

While hands-on dissection is no longer part of the process, many art programs including the New York Academy of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, and the Florence Academy of Art still incorporate écorché studies into their courses.

This practice of curiosity and inquiry, which has existed for over a millennium, lives on through Écorché Studios and all that we strive to do. Click here to find out more about how you can get involved in upcoming workshops, classes, and exhibitions.

If you would like to learn more about écorché, including its more recent history and applications in contemporary art, please consider joining our mailing list.

Sources

[1] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “écorché,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/art/ecorche.

[2] “Theory - Anatomy,” The History of Creativity, accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.historyofcreativity.com/sid1242/theory--anatomy.

[3] Uriél Danā, “Écorché: The Art and Science of Seeing Through Others,” Uriél Danā Fine Art, July 1, 2019, accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.urieldana.com/articles/art/ecorche/.

[4] Sanjib Kumar Ghosh, Human cadaveric dissection: a historical account from ancient Greece to the modern era, September 22, 2015, accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4582158/#B14.

[5] Naren Katakam, “Michelangelo's Moses and his little finger,” Naren Katakam, Nov 11, 2021, accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.narenkatakam.com/moses-and-his-little-finger/.

[6] Roger Jones, “Leonardo da Vinci: anatomist,” The British Journal of General Practice, June 2012, accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3361109/.

[7] Dan Scott, “Écorché,” Draw Paint Academy, December 17, 2019, accessed January 25, 2023, https://drawpaintacademy.com/ecorche/.

[8] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Andreas Vesalius,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andreas-Vesalius.

[9] Uriél Danā, “Écorché: The Art and Science of Seeing Through Others,” Uriél Danā Fine Art, July 1, 2019, accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.urieldana.com/articles/art/ecorche/.